I have two teenage daughters who swear to me they will never have children. They say that they, like all children, are a drain on the life of their mother. Why would they want to put themselves through that, they challenge us to answer. I have nothing to say to this. We men may be loving fathers and husbands but cannot be mothers. We can only sit a little apart, loving the mothers in our lives, not really understanding the true nature of their connection to their children. So I just watch and listen to my wife Jenny who dismisses her girls’ vows with a smile and few words.

What can she say, really? What can anyone say about why children mean so much to their mothers without relying on platitudes or abstractions? Words are inadequate to the task.

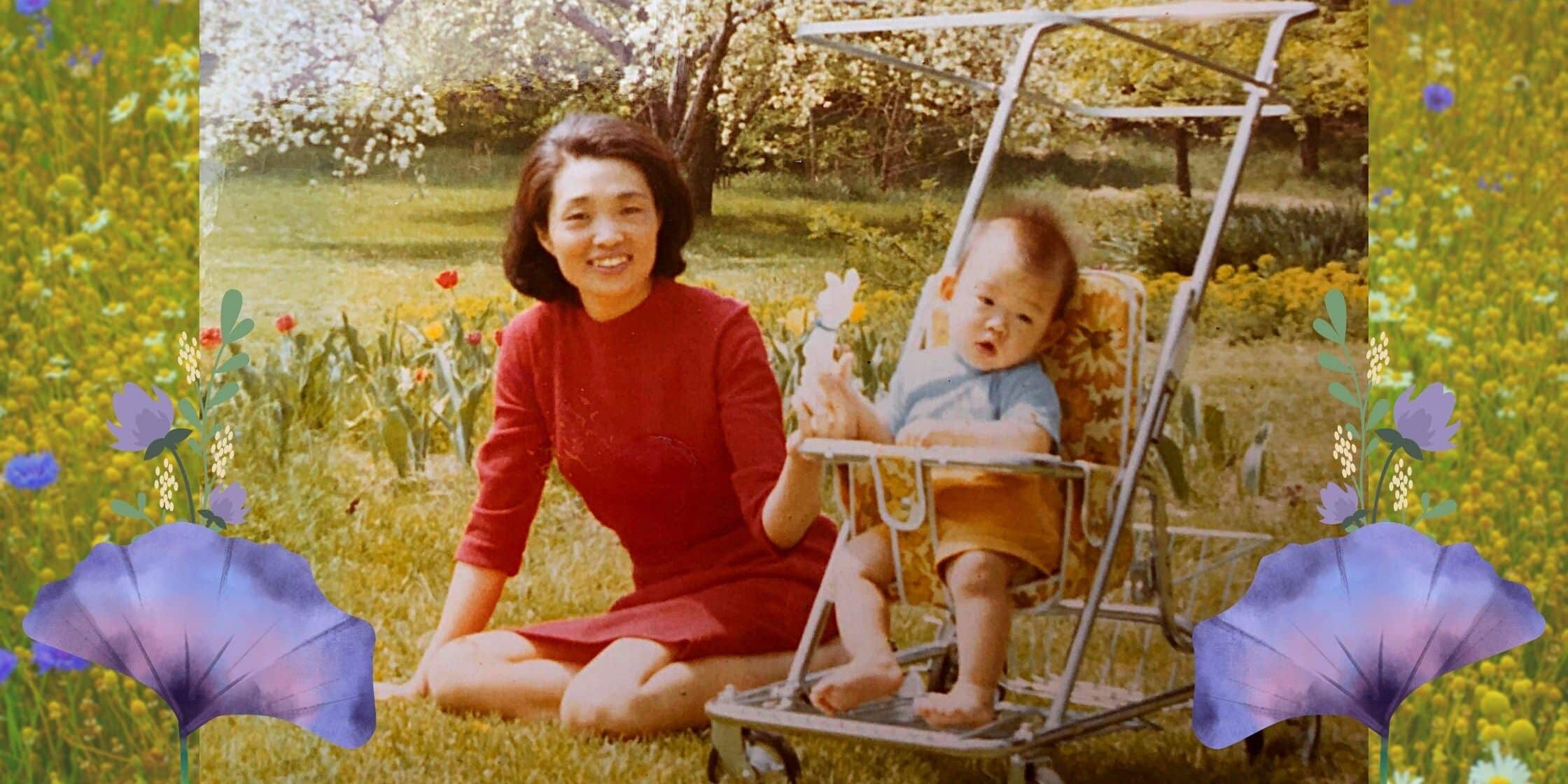

We have only images that help to describe the essence of this relationship; recollections, and deep – even painfully felt – gratitude. If a single word could capture motherhood, children think of sacrifice. What is unknowable to them is the private trove of rewards mothers may treasure.

I think of my own mother and wonder whether the sum total of the pleasure and meaning she derived from being my mother could possibly have offset her sacrifices for us. Recounting her life, I cannot imagine that it could. Nor do I think it matters to her.

The strongest memory I have of my mother and me is our hurried walk through the gleaming airport in Pittsburgh almost 54 years ago. We were newly arrived from Korea, about to meet my father whom my mother had not seen for seven years. With me and my older sister in tow, she walked briskly, trying to keep up with the American flight attendant. The American had taken it upon herself to lead the shy mother of two through the maze of points where immigration could be cleared, bags reclaimed, and families rejoined.

I remember the squeeze of my mother’s hand, anxious for her boy to keep pace, anxious for countless other reasons. It is hard to conceptualize the turmoil the 34 year-old woman must have felt in that moment. About to confront life in a land she could not fathom, she was now severed from a world that had once enveloped her with glowing familiarity.

She was no stranger to hardship. She was the second of three daughters to an evangelical minister. He and his wife (the grandmother we all knew as “the Tiger”) endured the indignity of Japanese-occupied Korea, the physical persecution of Christians, and the death of another beloved daughter to impoverished illness. As a family dependent on the meager income of a minister, they had lived most of their lives with very little. Growing up, she had been terrorized by the threat of death in war, the periodic imprisonment of her beloved father, uncertain of his return.

She rarely talked about those times and it was all I could do to recreate the period from myriad other sources. I learned from my aunts that even as a young woman, my mother avoided social engagements, preferring to escape to a quiet place for painting and singing hymns. Admired for her beautiful voice and artwork, her parents saved to send her to the storied Ewha University. She was sought out for her sensible judgment and empathy, an unjudging comfort for others in need.

I wrote an essay in this column last year about my unusual father and won’t dwell on him here. Suffice it to say, his was not an easy life nor he an easy man. My mother could not have known when she first met the strange young man who had raised himself from the ashes of the Korean war how far he would take her from the comfort of her extended family. No sooner was I born than he carried out his plan, at the urging of my maternal grandfather, to study for the ministry in the United States.

With the help of her parents, my mother raised her two children alone in Seoul. Yet, I imagine her happy then. If life was hard, it all was familiar. The raucous adventures I shared with my many cousins were possible because my mother gathered with her sisters often. The incessant gossip, the simple food, the moral lessons, all wrapped themselves together in my mind as an image of community and thus joy. My grandmother was a dominant, loving force, around which my mother and all our lives swirled. The devout faith in God that suffused that extended family and that place was as permanent as prayer before each meal, each bowed whisper to God before bed.

When we landed in Pittsburgh in 1967, my mother found herself as far from that home as it was possible for her to be. After the flight attendant left us in the airport with a reassuring smile, I saw that a man stood there waiting. My father, I learned.

My mother would shortly discover that, as a university professor, her charismatic husband had become so integrated into American life, he was the life of the faculty parties with his cutting humor, adroit conversation, chain-smoking and free drinking. Most shocking to her, though, was that he had not only betrayed his intention of joining the ministry but had transformed into an atheist.

I only imagine the vertigo she must have experienced, like so many other immigrant mothers who come here, where everything is unnavigable, where every word spoken, even the simplest, is a cause for anxiety and opportunity for shame. The impatience, condescension, resentment or worse, in every glance. When all that is sharpened by deep anxiety for their children, what must be the misery of such women? They not only find themselves suddenly incompetent but must send their trusting children into a world they cannot grasp.

Many immigrants move into a community where they can at least support each other and make themselves understood in a common language. But my mother lacked even that thin lifeline. In the farthest western reach of Pennsylvania, she was isolated from any other Koreans, and she lived in the house of a man who was functionally a stranger to her. Within days, she fought him about the stench of cigarettes, his tempestuous treatment of her children, and his refusal to worship God with her, and much else.

I have no doubt whatsoever that, but for her children, my mother would have returned to Korea within the year. She stayed because she dreamed of a future for my sister and me here. I suspect that’s all that sustained her. That and her faith in God.

I never once heard a complaint from my mother about how she missed her home, her own mother, or how lonely or unhappy she was, trapped in this circumstance. A crucial feature of her sacrifice for us, it seems, was that we were not allowed to know its full dimension.

Thus, apart from images of her arguing fiercely with my father in the early years, my childhood memories are a blur of forced regularity and uneasy calm. Her quiet prayers, the reliable rhythm of her getting food ready for us, her never being sick, her poring over figures and coupons as she sought to stretch the income of a junior professor, her teaching herself English with a nearby dictionary, her beautiful singing in the Anglo Protestant church every Sunday when Ruth Nicely would come to take us.

The routine in time’s passage makes new memories, and I hope she found some of them beautiful. She gave birth to my younger brother one year after our arrival in the United States. “Johnny,” this American was fittingly named. She took us to the chestnut tree she had discovered in one of her solitary walks, gathering the fallen bounty in autumn. In summer, she would walk the length of local woods gathering a kind of plant that grew wild so she could make stock for vegetable soup. She fermented the crabs we caught during seaside vacations in soy sauce. For the panfish and bass caught in lakes, she taught me to salt them with just the right measure, wrapped for freezing, and roasted in the winter for a simple feast with rice and kimchee.

And then, suddenly, I remember her being happy. Some 15 years after our arrival to this country, my father turned back to embrace Christianity with his typical single-mindedness. He went on to be ordained a minister. I was by then out of college, and so could not fully enjoy this new relationship in my childhood home. But during my visits, I found my father gentle and my mother laughing with him. She would scold him about those of his sermons she thought too complex, and trash talk him on the increasing occasions she beat him in chess. I glimpsed in holiday gatherings the household where a light-hearted woman made the meals and cleaned the house. She would turn to her children, prodding us to share our news.

Her joy compounded when her grandchildren began to fill that house, their innocence drawing her in to see the world anew. When my mother and father came to our cabin in the mountains, she would disappear into the woods returning with a pail of black and blueberries. She and my Jenny spending hours just talking. She left there the three wooden stools she lovingly painted with delicate flowers for each of my children as they were born, their names etched, boldly for the boy and gracefully for the girls.

My mother is in her late 80s now, largely bedridden. When I call, I can tell she automatically strengthens her voice so I can only hear her chat effortlessly. If she is in pain, I will not find it out from her. She surrounds her bedside and walls with all the pictures my wife sends her of our children annually. My wife knows that gazing at them brings my mother a kind of happiness that only they fully share.

I don’t know if the sum of these joys offsets the mountain of sacrifice she made for me and my siblings. All we can do is hope it is so, loving her and grateful for every good thing in our lives.