Revolutionary Artist Remembered in a Luminous Documentary Narrated by Steven Yeun

Called “the Nostradamus of the video age” and the “father of digital art”, Nam June Paik was lionized for his visionary artistry decades ago. But now? His foundational contributions to digital pop culture have largely faded from collective memory, outside the art world. Amanda Kim’s remarkable film, “Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV”, corrects that deep wrong.

Paik’s work is currently on permanent display at the Smithsonian in DC and is also showing in Seoul at the Nam June Paik Art Center. There have been past exhibits at MoMA, the Tate and pretty much every modern museum of note across the globe. But Kim’s documentary showcases the, somewhat forgotten, renown of an artist named as one of “The Century’s 25 Most Influential Artists” in 1999 by ARTnews. And if you’re old enough to remember Absolut vodka’s omnipresent wallpapering of pop culture from the 80s to the aughts, “Absolut Paik” was right there alongside “Absolut Warhol” and “Absolut Haring”.

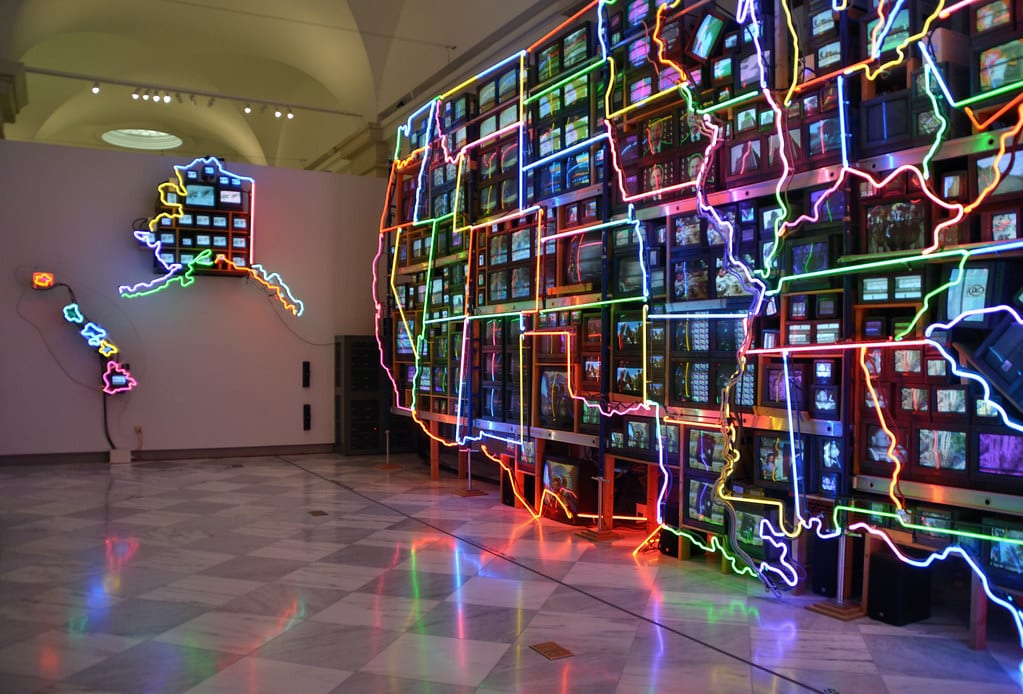

The term “electronic superhighway” was coined by Paik in 1974. But friend (and former director of the Whitney Museum of Modern Art), David Ross, believes Paik’s foresight into how the internet would evolve was even more prescient.

“I remember one night being awakened at 3 in the morning by Nam June saying, ‘I was wrong, it’s not an information highway. We’re in a boat in the ocean and we don’t know where the shore is.’”

A year before Live Aid, on New Year’s day in 1984, Paik’s “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” reached over 20 million people all over the world as a live satellite show. It was hosted by a drunk George Plimpton, with contributing segments by “extremely stoned” artists such as Allen Ginsberg and John Cage and a song by Tears for Fears. One show producer lamented the bad performances, delay and sound. But Paik laughed in response and refused to agree that the show was “a disaster.”

“[What matters] is, we did it… That we failed here and there does not really matter. [Failure] is more interesting,” said Paik. Earlier in his career, Paik observed that “newness is more important than beauty… Anything which is radically new is worth trying… like a scientific approach.”

“Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Unexpected Origins

Born in 1932 to a wealthy, early chaebol family, Paik “loathed” his father and strove to become the opposite. Growing up in Seoul during the Japanese occupation, Paik didn’t suffer the financial hardships felt by the majority of Koreans at the time. But far from being a comforting haven, home was an unhappy place of capitalism gone amuck where his “badly treated” aunt worked as a maid. Self-identified as a Marxist in his youth, Paik left the country when the Korean War started and lived in Hong Kong and Japan. He moved to Germany after college to pursue music and didn’t return to Korea for 34 years.

Earning a PhD in music and philosophy, Paik could have become a concert pianist but instead he tried his hand at composing. It was in Germany that Paik left music as a profession and became entranced with the avante-garde art world. In his own words, it all began upon meeting John Cage, who became a lifelong friend and mentor.

“My life started in 1958. 1957 was B.C. Before Cage,” wrote Paik.

Early Struggles

While in Germany, Paik explored a fascination with television and his first gallery show in 1963 was called “EXPosition of music, ELectronic television”. It featured tv towers and also interactive tvs where images could be changed and manipulated by show attendees. He moved to New York in 1964 to be in the “communications capital of the planet”.

Early critics of Paik’s shows in Germany and New York were not kind. He was even arrested for indecency when one of his shows featured a topless cellist. Feeling deeply discouraged by the lack of critical or financial success, Paik described his early New York years as “living like a beggar” and considered giving up on art. He wrote to Cage:

“I decided that when I’m fooling around still in my 40s as a yellow gypsy here that you had bet on the wrong horse.”

In response, Cage urged Paik not to give up:

“All those pieces are really elegant and charming… How it can involve technology in a livelier, more human way, that’s what I would say is very profound.”

After receiving Cage’s “greatest encouragement,” Paik resolved to keep going with his electronic art for at least six months and applied for a multitude of grants. In a fateful twist, an early critic became an avid patron.

“Open Your Eyes”

It was through a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation that Paik’s art truly launched into acclaim. RF Director Howard Klein, who as a New York Times art critic called Paik’s early work, “fraught with pretensions,” threw Paik a lifeline with a $15,000 grant.

“I was not interested in that kind of revolutionary art [of Paik’s early shows]. It didn’t reach me. I didn’t find it interesting or important. However, when I saw what he was doing with television, I thought it could have a tremendous benefit to a large number of people,” said Klein.

The grant funded Paik’s groundbreaking work in digital manipulation as an artform. Paik bought studio time at television stations and used powerful magnets to distort and re-shape electronic images. Station producers hated working with Paik because his whole intent stood in direct conflict with their desired purpose of amplifying crisp, clear images. Later Paik, with no formal engineering background, created a “synthesizer” to more drastically generate and manipulate both moving and static images.

Even then, fellow artists recognized Paik’s genius. “Basically, what Paik did was alchemy. He moved the screen from being something plastic or concrete and he liquified it so that it was all malleable,” said artist Shalom Gorewitz.

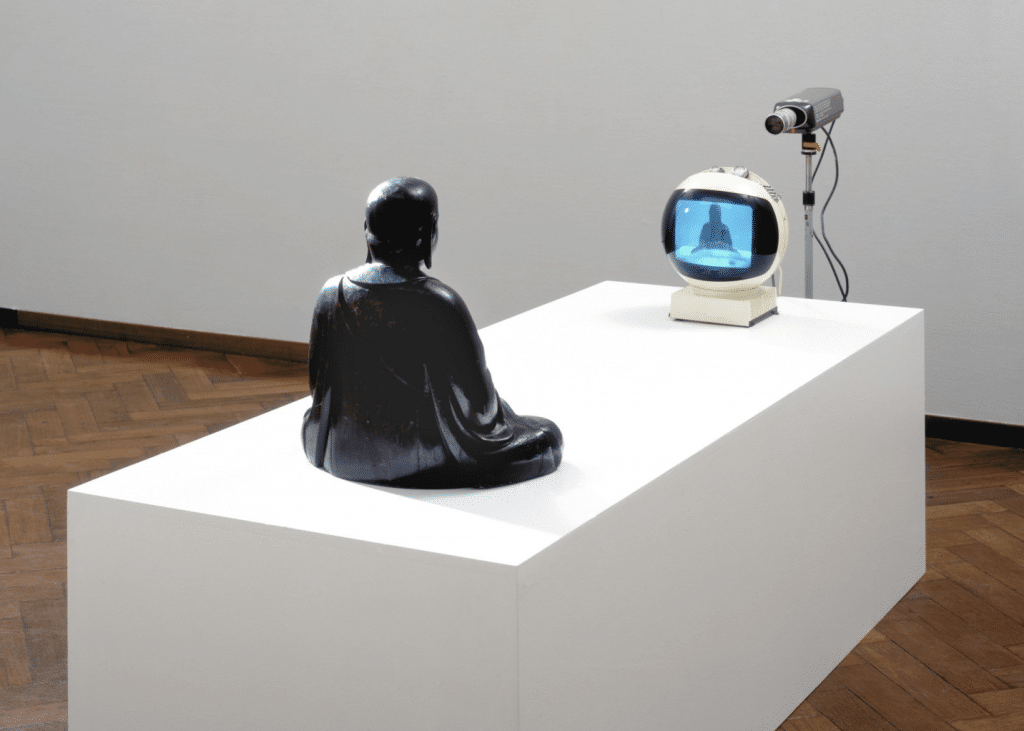

Revitalized, Paik found commercial success with variations of “TV Buddha”, installations that featured statues of Buddha watching himself on TV. His roommate, and secret spouse, Shigeko Kubota, joked, “He made so many buddhas because they bring him money… buddha, buddha, buddha.” Towards the end of his life when he was in failing health, Paik mused, “Buddha is punishing me for what I did to it.” (A few renditions of TV Buddha displayed the figure smoking, wearing headphones or decapitated.)

In 1982 the Whitney celebrated Paik’s work and held its very first retrospective honoring a video artist. Although finally appreciated by the art world and called in headlines: “The Zen Master of Video” and “The Picasso of Video Art”, Paik still struggled with racism and his own feeling of not belonging anywhere.

“Most Asian faces we see on the TV screen are either miserable refugees, wretched prisoners or hated dictators,” said Paik. When asked in Seoul in 1984, “Have you always felt that you are Korean?” Paik answered:

“Well, depending on where I am. In New York there are lots of Koreans, so I feel like a New Yorker. In Long Island there are fewer Koreans, so I feel Oriental. When I’m in Germany, there are no Koreans, so I’m Korean. It depends on the place.”

In fact, it was to his utter surprise that he was given a hero’s welcome and greeted at the airport with thunderous applause after his first trip back to Korea in 1984, after 34 years away. It’s interesting to note that Korea had by far the largest viewership of “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” at 6.8 million even though it aired at 2 am. (In contrast, the combined US/Canadian audience was 3.5 million.)

“Jacob’s Ladder”

In 1996 Paik suffered from a stroke and until his death in 2006, he remained in poor health. But his final show in 2000 at the Guggenheim, “Jacob’s Ladder”, dazzled. Heralded as a masterwork, it was a spectacular laser display that zigzagged from the floor to the ceiling of the Guggenheim rotunda, “literally like a spear of light grounding the earth and the heavens.”

“Jacob is the Biblical trickster and Nam June Paik was a trickster. This is the moment where Jacob has an awakening and wrestles with the angel of God… He’s ascending the rungs and at that point he’s leaving his tricksterness and becoming a sage… That was Nam June Paik, from trickster to sage,” said Gorewitz.

Kim’s documentary premiered at Sundance in January and had a limited theatrical release in March. Narrated in part by Korean actor Steven Yeun, “Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV” can now be streamed on PBS in their American Masters series.

“Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV”

American Masters, PBS