“She says she remembers it was September when you came to her, because the cosmos flowers were blooming.”

Cats are very good at making themselves comfortable. My pair curl up, on or in any space possible, whether it be a soft, fluffy pillow, or a pile of important paperwork. But they’re still suspicious about why I’ve been home so much for the last six months, a strange pause on a life I usually keep as busy as possible.

What to do in this odd new world?

I made cakes for holidays spent with family on Zoom instead of in person, thus faced with the prospect of eating entire cakes alone, learned how to make hand pulled noodles from scratch, sewed masks until the sewing machine jammed and failed at two repair efforts.

The passage of time and seasons was marked by the growth and changes in my houseplants and a friend who reminded me what day of the week it was, but I couldn’t ease myself into any semblance of peace.

Babies are very good at getting themselves attention. They cry out for help with what they can’t understand or otherwise express. When someone consistently arrives, babies learn assurance and confidence: someone will come, someone will be here, I am not alone.

When a caregiver provides regular meals, changes diapers, makes eye contact, mirrors smiles, rocks you to sleep and rubs your back when you’re sick or tired or scared, these affections trigger the release of oxytocin and endogenous opioids, calming brain chemicals and natural painkillers, which lower the stress hormone cortisol. Eventually babies under such care feel secure enough to learn how to soothe themselves.

Conversely, if the cries go unheeded, babies can learn hopelessness instead. They may even stop crying altogether, not because they are consoled, but because why call out when no one is coming?

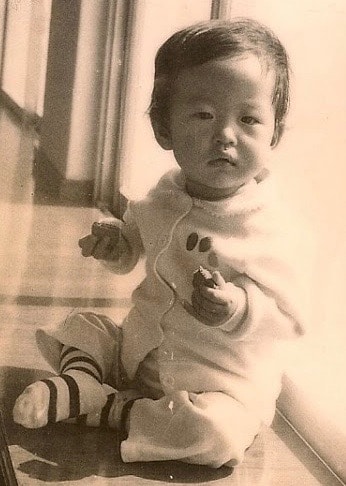

The first nine month of my life are a blank. I can conjure up many possibilities to fill in for the lack of information, but I know there are many more I’ve never even imagined.

I wonder about my birth mother and how much time we spent together. Maybe we lived in a quiet house so she kept the TV on for company and I giggled with her at funny movies. Maybe we lived with the love of her life, and they slurped spicy noodles, wiped gochujang off each other’s cheeks and danced in the kitchen. Or maybe she cried and I worried about her even then. In studies, babies have been shown to detect and absorb the stress levels of others and even feel empathy at a very young age.

My South Korean adoption paperwork begins with an elderly couple. When they brought me to Angella Orphanage, they said they found me on their doorstep but were too old to care for me. After three months in the orphanage, I went to live in a foster home in Seoul.

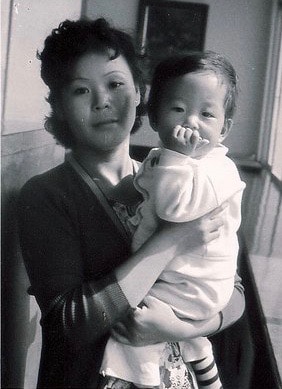

“She says she remembers it was September when you came to her, because the cosmos flowers were blooming.” So translated the Korean social worker when I reunited with my foster mother in 2008. “She says you still have your baby face.” It was my first ever in-person account of my history.

We held hands while she told me that when my plane took off for America she held my blanket and cried, that she’d wanted to keep me but couldn’t afford to, that she couldn’t handle taking care of another child after me.

I never thought that anyone from Korea remembered me, missed me, or cared about me. I even wondered if she was my birth mother but didn’t want to tell me.

When people ask where my “real” parents are, I show them a picture of my Russian American Mother and Italian American Father. I think of the books she read to me when I was little and the bigger books we can discuss now while we’re making crafts and cooking together. I think of the songs he sang while he tucked me in so I wouldn’t have to fall asleep alone, and how we now share a passion for lists and projects and comparison online gift shopping.

More than blood, all of these things and more go into parenthood, even with a child who’s all grown up.

I worry. I worry about them all the time. I worried before we lost someone to the virus and even more so now. I call them often, carefully ask how they’re feeling, remind them to wipe down their groceries and practice social distancing.

And I worry about my family in Korea, where they are, if any of them are left, if they’ll be alive long enough for me to find them.

To borrow from Moulin Rouge: “Days turned into weeks, weeks turned into months. And then, one not-so-very special day” I made a flower out of paper. I had been following the designer on social media for years, and for some reason that day the paper and scissors called to me. The next day I made another and in the days that followed many more.

I posted pictures for fun, sent a few as gifts and started running out of places to put them. Then requests came in: for birthdays, anniversaries, house warmings, for the passing of a beloved pet, a cake topper, a bouquet to cheer someone who had contracted the virus but recovered and for just the joy of having something pretty in the house.

As my hands measured and snipped, shaped and taped hundreds of petals, my mind calmed and focused, at least for a while.

So, how do we deal with the constant barrage of ever shifting dire topics competing for our attention and anxiety and hearts each day, each hour, each minute? Everything feels vital and immediate; it’s impossible to know where to begin.

Everyone is navigating the insanity of this time in their own way. What soothes and comforts someone else may not work for you and vice versa. In fact, something that worked for you in the past may even need a refresh.

Instead of thinking about what we want to do when this is “all over” and things go “back to normal”, let’s find what we can love about right now. Every day we get another chance. I personally believe in that even without a pandemic.

Be safe. Be kind. Wash your hands. Practice social distancing. Mask up.

Wishing you health and safety and peace.

Selected excerpts are included from entries in the Korean American Story ROAR Story Slams 2016 and 2019.