It is September, and there is a special group of parents across America who confront a certain sadness. These men and women see their first borns leave them for college. The children disappear around the corner of a campus walk or into the recesses of a dormitory, leaving their parents to silently experience the sad-happiness-pride-anxiety that sweeps over them. Their core objects of love for the past 18 years slip away, moving into new-found and private worlds.

My wife and I felt this last week as my son awkwardly said goodbye, wishing to end the prolonged departure so that he may begin his new life. As I looked squarely in his eyes before giving him a last, rough hug, it was harder for me than I expected. It was not just that I would miss seeing him, I felt regret and looked for solace.

The bitter-sweet sadness must be common to all parents, for the departure marks the loss of a precious child to a careless world. But I wondered about this sense of regret that sat heavy in me. I tried to identify its nature and to locate its source. All I could come up with was the vague notion that we were not as close as I had always expected us to be. I had expected to be the kind of father my son would love and trust as one who unquestionably loves him in return. As he said goodbye and I saw the shielded distance in his eyes, I regretted that I had not managed to forge such a bond.

I wondered whether this regret is one commonly shared by Korean American fathers. We are familiar with the famously awkward father-son relationships (especially concerning the eldest son), where the father practices a studied aloofness and distance from his boy, while the son maintains an almost worshipful respect for his father. I’m not sure where this strict role-playing comes from. Maybe it has its origins in the history of Korean economic hardship where a family’s survival depended on the fortitude of the eldest son. Emotional displays might weaken the son’s character, which could in turn make him less fit. The Confucian division of roles within the model society likely played a role as well.

Whatever the source, this relational characteristic seems real as we see it immigrating here to the United States. The rigid division between fathers and sons could even deepen for Koreans who arrive here uncertain of their ability to survive financially. Most Korean American men of my generation will recall their uneasiness when sitting with their traditional Korean fathers. Each will have a different story about how the tension was expressed in his boyhood home. Some will talk about fathers who became even more stern and distant as the weight of immigrant life bore down on them. That was surely true in my father’s household.

As the product of such homes, we Korean Americans think to ourselves that we are free to redefine the father-son relationship. We will ensure different, more emotionally satisfying, ties to our sons. But I found this more difficult than imagined. The imprint left by our fathers – not to mention social expectations – is not so easily shed.

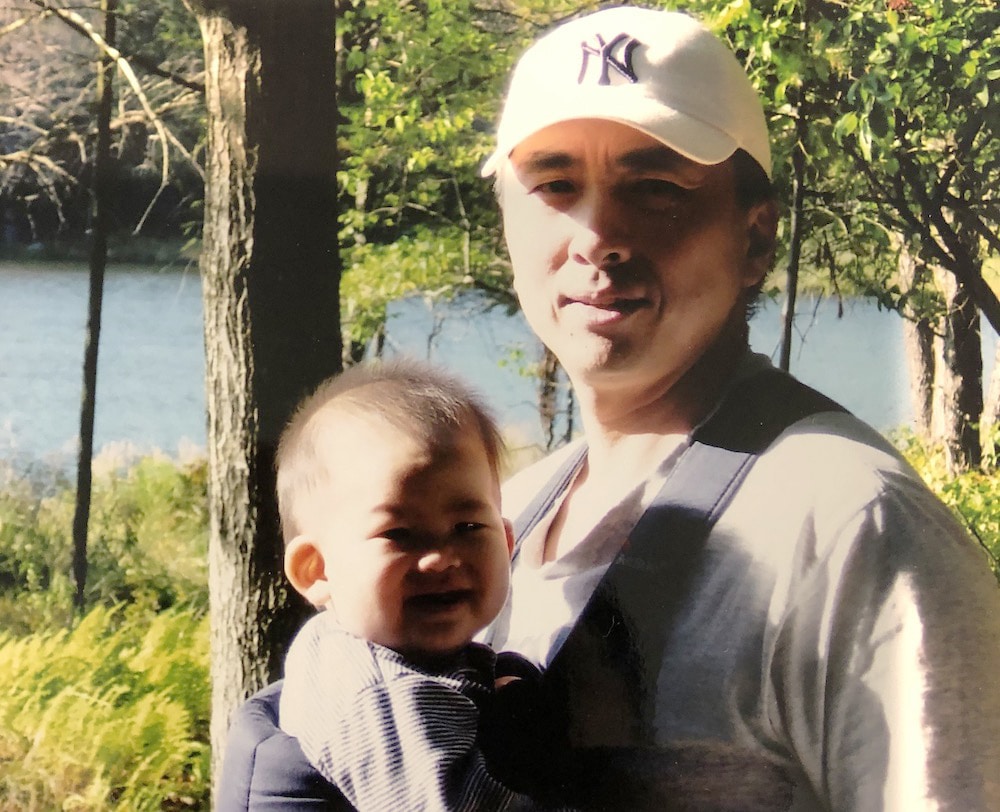

Years ago, when he was no longer a little boy, my son gently extracted his hand from my hold as we walked down a street, signaling for the first time a physical drawing away. I had cherished the countless moments carrying him in the baby bjorn, on my shoulders, offering a human jungle gym, or the manta ray in the pool. Knowing that the physical closeness parents enjoy with their small children will eventually end did not make the first moment of him pulling away any easier.

I thought I could replace the wonderful closeness that is lost in that moment with an open and loving relationship where my son could confide in me, want to be around me, ask to go fishing or to a movie. After all, we had spent countless precious moments doing such things together when he was small.

But I failed to create this relationship because, as I now reflect, I was too busy readying him for all the hardships I imagined to be in store for him. I saw more flaws that needed to be corrected; I instructed more and shared less. Naturally, he, in turn, pulled away more than his hand, and closeted his heartfelt thoughts from me, freeing his imagination and aspirations from the constrictions of a lecturing dad.

I don’t know that I could have done anything differently. We too readily fall into the role of being “strong,” stoic, and disciplinarian. Even if financial prosperity is no longer our goal and is replaced by our desire for our children to be kind, creative and confident humans, it is still a father’s goal, pursued in father-like ways. The many lectures, opportunities for teaching moments and lessons, rebukes and expressions of disappointment, mount up and calcify. In the process, the hope of being a father who is a warm and easy presence for our children is at risk of slipping away.

All the while, we think that our consistent expressions of support and love will counterbalance the periodic and stern lessons. But I found they don’t and really can’t. At the end of the day, we may succeed in winning the respect of our sons as reliable guides, but the comfort of a loving relationship goes missing.

And then the day comes, as it did last week for me, when the boys say goodbye to us on college campuses. The vague regret I felt was my realization that there will be no going back to the times when I held him close to me, no chance for a do-over, to be a more accessible father than I had been.

For a few minutes, I say to myself that I gave him at least the wherewithal to be strong when adversity hits as it inevitably will. Sometimes in an unending barrage. But then I realize this was no more than my tough Korean father’s legacy had been to me. I had hoped to offer more than that for my boy.

I said earlier that, with my sense of regret, I looked for solace. Ironically, I found it reflecting on my own relationship with my father during his later years. As I grew into a man, we shared more and I drew far closer to him than it was possible for me to imagine when I had been a boy in his home. It turns out there is some wisdom in the ancient Korean tradition that assigned rigid roles for fathers and sons. It implies that the boy going off to college is not the end, but a new and intriguing phase as boys become men, on whom we can lean for comfort. We each become free to share experiences as co-equals, bound by the love that was there but, for many years, unexpressed. We may no longer need our grown sons for financial security, but they offer the deeper reward of a shared life and profound kinship.

I miss my son no less but now wait with anticipation for the man he will become.