Joseph Han is the author of Nuclear Family (Counterpoint Press, June 2022) and a 2022 National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. A recipient of a Kundiman fellowship, his work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Nat.Brut, and Catapult. Currently, he is an Editor for the West region of Joyland Magazine and has a Ph.D. in English & Creative Writing from the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa. He lives in Honolulu.

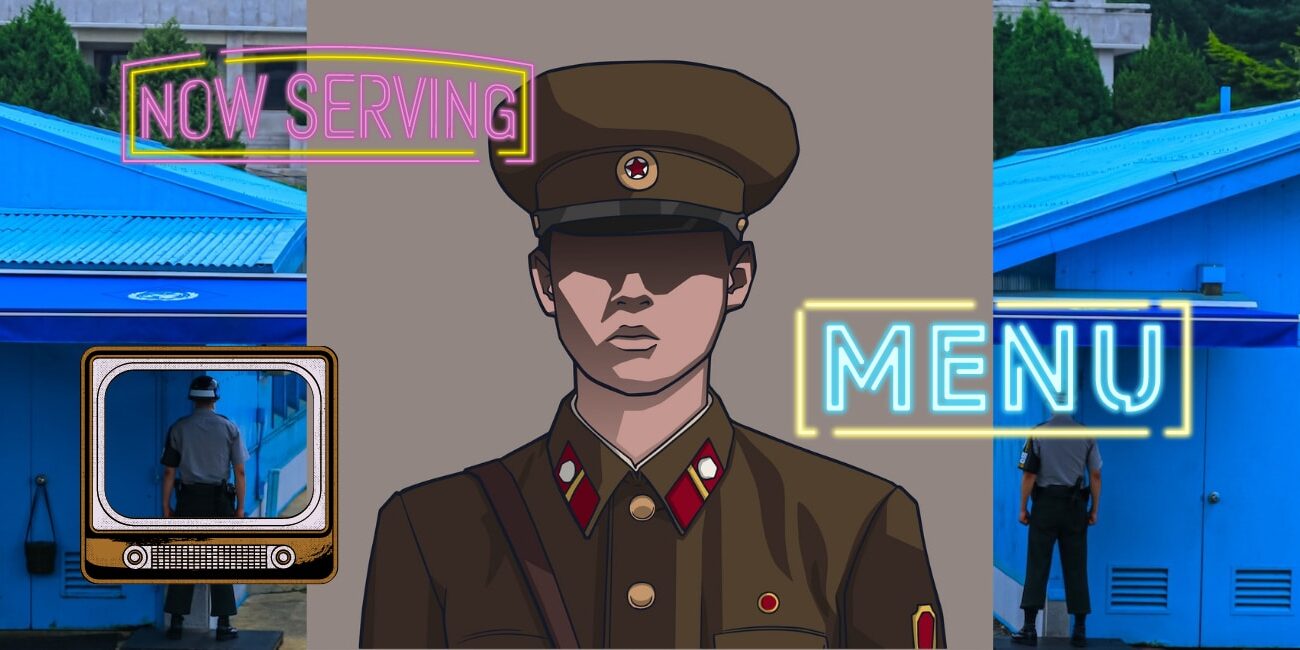

The Cho family of Hawaiʻi runs a chain of Korean plate lunch restaurants in Honolulu, which found success after being featured on the TV program of a celebrity chef. Their world is rocked when their son Jacob, who was working in Seoul as an English teacher, tried to run over to the North Korean side while on a tour of Panmunjum at the DMZ. His younger sister, Grace, and their parents are utterly at a loss as to explain his actions. As they anxiously await news of Jacob’s fate—shot by a South Korean soldier, arrested, and possibly facing charges—they must also deal with local repercussions as they are now held in suspicion by the Korean American community and the rest of the world.

The following is an excerpt from Nuclear Family:

Grace

Her parents babbled as she ate a whole pack of gim, in stacks rather than individually, the salt stinging the cold sore inside her lip. Grace clutched her stomach. She was stress eating a bag of tangerines a day, leaving a trail of dried-up skins torn open into stars, a tower of empty diet ginger ale cans and Appa’s remaining stash of Hite on her desk. Grace only ate a spoonful of swamp soup, what she called miyeokguk for being so slimy with seaweed. For dinners, they typically had some kind of soup with rice, an effort to save money, when all Grace wanted was a reason to floss until her gums bled, a steak or microwavable ribs like those Cho Harabeoji used to throw in the oven despite Cho Halmeoni’s protests, who’d rather Grace ate a boiled egg or gogoma. Not to mention the king crab legs dipped in melted butter he’d share with her some nights, whenever Grace was dropped off at her grandparents’ with her brother.

Forever on the subject of her brother. Umma called a family meeting after clearing the table, frowning at Grace for not eating. Sobbing had made Umma’s face puffy. She pounded her hips as she walked around their living room in a white gown and pink cardigan, blue gel mask on her face, growling about how Grace let this happen. Their son had been shot. Thankfully, it wasn’t fatal. There was no report on which side fired, where Jacob was hit. North Korea denied culpability while suggesting this was an act of aggression on the part of the U.S., and pundits insisted the north fired, much like history argued about who instigated the Korean War. The world held Jacob with suspicion. Sleeper agent. Stunt.

Grace squeezed the velvet couch pillow in front of her, gouging the spots where its eyes would have been. Appa sat on his flaking leather recliner with his arms crossed, wearing one of Jacob’s old Eckō sweaters. Umma had not been this unsettled since Grace shaved the sides of her head the week Jacob left, which she maintained to Umma’s dismay.

“Jagiya, don’t you agree? If Grace found out why he was going there, she could have talked him out of it.”

“Hmph, yes,” Appa said. “You never know.” “This is pointless.”

They’d been having a version of this conversation for weeks now. The subject of lawyers, the embassy, and hoping for the latest update from Jeong Emoh, the sister Umma had not seen since she left South Korea twenty-five years ago, winding down the evening with how Grace was at fault.

At first the regulars showed up, such as Uncle Keoni, who used to pick up trays of galbi for a beach-park family function or grad party. Or Aunty Lin and the plates of barbecue chicken for her boys in Little League. Easier for them to turn to other options, but harder for Cho’s to compete with the overpriced Sorabol down the street or the Korean supermarket that had opened nearby. Colloquially referred to as Koreamoku for the area’s spattering of Korean-owned businesses, the neighborhood once held Cho’s at its center. Appa so proud he believed Cho’s inspired the measure to designate the neighborhood the official Koreatown of Honolulu, which never came to fruition. To the Korean community, Cho’s was more a local cafeteria. Barbecue chicken was not KoreanKorean food, and neither was meat jun. What Cho’s served wasn’t unique but familiar. The plate lunch contained a table of foods organized for one, the excess of sides never-ending at Cho’s, the potluck purgatory.

Gradually, since the incident, regulars showed up less. Even their usual group of construction workers, bursting in with their fluorescent-yellow long sleeves and laughter, drawing out Appa to flip channels to whatever game was on. Some phone orders came in, a number of prank calls and threats telling Grace and her family to go back to North Korea if they loved Kim Jong-un so much. We couldn’t if we wanted to, asshole. Customers paid and left. No one stuck around longer than they needed to.

Grace stood up to leave. She knew what her parents couldn’t admit: they were done. The public was not without options when plate lunches were all over like gravy ladled from the melting pot even Grace couldn’t resist submerging in for a quick fix.

“Where do you think you’re going now? At this hour?”

Grace motioned to her home outfit of sweatpants and an old shirt from middle school to say nowhere. Umma often admonished Grace for her appearance, for dressing in baggy clothes and jeans like a boy, wondering out loud why Grace didn’t have many friends, maybe it’s because she didn’t look more like a woman. Grace surprised herself on days she put on clothes and went outside voluntarily.

“Now that I think about it, since Oppa got pretty close, I think I’ll have what it takes to get through and make it to North Korea.”

“Ddal,” Appa said. He frowned, having promised not to tell Umma about her panic attack upon watching the news.

“I heard Pyongyang is pretty cool. Maybe I’ll be able to catch those choreographed

shows.”

“Ddal, I said why are you so rude to your umma?”

Umma muttered to herself and walked away. Grace groaned and got up to make a cup of Sleepytime tea in the kitchen. Umma came back with the blue briefcase holding her cupping set.

“Eun-hye ah, I need your help.”

The sciatica was too much for Umma. She had no strength in her legs and couldn’t afford to sit or stand for too long. She hobbled with a hand on her hip at all times. The lower half of her body occasionally got numb and prickly sharp with pain. Umma needed Grace to cup her back in order to draw out the bad blood in her system and improve circulation. Umma called out the areas she wanted Grace to suction with the glass cups and hand pump. Grace would have to use the needle pen so dark maroon blood could collect in the cups, viscous and slimy like the kind of stuff vampires would put on their toast if they were morning people. She’d have to catch blood from each cup and wipe Umma’s back and disinfect the whole set. Grace hated doing this. Umma had never asked Jacob, not wanting to be a bother.

“I’m tired,” she said. “Appa can help you.”

Grace went to her room. She stretched her right shoulder by leaning against the doorway, careful not to spill her tea. The pain in her neck and arm were getting worse. Grace couldn’t sleep without waking up to the sudden rush of pain vibrating through her limbs. She could’ve used cupping herself if it weren’t for the pepperoni blotches it left all over her body. Her room was smaller the more it cluttered and remained this way—old bags she never used piled in a corner; leis from high school graduation hanging on the corner of her bookshelf, which was full of used copies hoarded from BookOff; and a growing mound of clothes on the floor to dig from: a collection of flannel and jean jackets she had no business wearing except indoors or on solo trips to Consolidated Theatres, which she couldn’t bring herself to do anymore.

She stared at the tea bag spinning over her cup. She had already read up on the news, since her parents never stopped asking for updates. She was tired of helping them make calls leading nowhere. The national news covered how Jacob was detained by the South Korean government and faced prison time. The United Nations military command issued a statement that the South Korean military would remain ready in the event of provocation by North Korean forces. Having participated in the protests for democracy, her uncle Samchun told Grace stories about the government torturing students and anyone suspected to have ties with North Korea in the decades following Gwangju. An article briefly mentioned that Jacob’s physical and mental health were unstable—he would need to be admitted for further evaluation. When Grace gave them the update before dinner, Umma dropped to her knees and startled both Appa and Grace, who caught Umma before she fell on her forehead.

To her parents, being Jacob’s sibling was not so much a bond as it was a handcuff, Grace guilty by association and humiliated anytime she saw a meme making fun of Jacob, a GIF of the moment he ran for the border, with captions:

When the parents aren’t home and she says “come over.”

When McDonalds announces the McRib is back.

When you realize you left the stove on.

Running from my problems like.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to disarm the North Korean nuclear program. You must covertly enter . . . “I’m on it.”

Grace’s brain worked like a stadium of connected flat screens, and at any given moment they all depicted some random disaster resulting from her usual awkward and clumsy behavior. She had her own penchant for tripping on sidewalks and curbs, down flights of stairs; she was often bruised from unknown sources but mostly the same bed frame corner out for her shins. Anything could go wrong, and at the most inopportune moments, the opening guitar riff of Triple D screeched through her head, louder this time as the video of Jacob looped on all screens. When Grace managed to roam about outside, occasionally she thought about walking into traffic or falling from the sky until a whiff of someone smoking weed caught her off guard and had her frantically searching for the source, which brought her back to the realization that she could only kill herself if it was instant.

Besides, her parents wouldn’t want her to die, or allow it. If she lost an arm, her parents could give her a bionic limb that transformed into tongs. Umma would smack the shit out of Grace to cough up all the Dr. Choi pills she swallowed, was ready to catch Grace before she hit the ground, ready to dive into the water, yank Grace’s hair before she stepped in the street, and transfuse as much blood from her own arm directly into her daughter’s veins.

She couldn’t work with them forever or age into the next Aunty Cho, or stick around Honolulu long enough to end up settling down and aspiring to a house in Mililani where they’d host their families and open presents during the holidays, Grace married to a mediocre-looking Asian man who probably worked for a bank, or at least functioned with the personality of an ATM and wore oversized Reyn Spooners to the many Japanese restaurants they’d go to on date nights to talk about nothing in particular over yet another side order of gyoza and pitcher of Kirin and eventually having the grandkid for whom Umma eagerly waited.

Not according to her plan, which was to get off this rock, strap an Acme rocket on her back to land in grad school as far away as she could get. She heard Umma’s cups clanging in the sink. Cabinets slammed shut. KBS News on high volume, Appa waiting to catch any update on that dipshit. It was obvious when her parents were upset. At any second Umma could burst in roaring with the vacuum as an excuse, somehow having caught a whiff through the double Ziplocs and the Altoids tin with a crushed-sticky-note filter inside.

Grace finished her tea with enough Advil, typically four or five, for a simple buzz in the meantime. She burrowed into her duck-feather blanket, sent to her from Baik Emoh in South Korea, and watched Instagram videos of cannabis influencers smoking out of liter soda bottles and mason jars. It had only been a week since she last smoked weed, a development arguably better than past habits sniffing markers and rubber cement under the lid of her desk, a trajectory that peaked in a brief life raving and a drawerful of Kandi bracelets, tapered down to a dwindling stash of wisdom teeth medication, led gently now to the foggy land of bongs and hotboxing David’s car. Grace preferred smoking with company, and it was always the excuse: good enough knowing someone who smoked and kept their own stash without having to commit to being a real stoner, anyone who seemed to need it more than she did.

She never hung out with David if it wasn’t going to lead to smoking. The same happened with Angela, the pink ice-cream pipe in parking lots, Angela blowing smoke through the crack in the window as Grace worried they’d get caught, their seats reclined all the way back as they leaned closer and whispered. Dried-up tangerine skins in the cupholder with pieces lined up on the dashboard. They talked about feeling like big fishes in a pond, Angela trying to convince Grace that Hawai‘i was too small for them both. Before Angela would leave for good to study abroad in Germany, before she moved to Colorado and got married, Angela texted Grace how she should’ve at least kissed her when they said goodbye: maybe Angela would’ve stayed and canceled the trip. Even if it were a joke, it wouldn’t have hurt less. It wasn’t clear to Grace what she wanted then, other than wanting to get tangled in Angela and her routine, when they used to be two sides to the same person. This didn’t stop Grace from choosing not to respond, despite previous plans they’d made to backpack around Europe—despite an email, much later, inviting her to come up to Colorado and get smoked out one day.

Always the language of ascension, as if it were beneath people to stay in one place for too long. Nothing wrong with being cordoned off in her room, on the Squatty Potty observing people smoke until her legs got numb. Better not to care. She guessed she was like her brother, who could retreat into himself instantly, behind the face he presented, polished of emotion when he gave his usual excuse that nothing was wrong—he was tired.

Grace knew what it meant to hide something that hurt and hollow yourself to hold it—to become a cave, no rush to crawl out. Sometimes it was quiet down there, until Grace heard a whisper: she could only rely on herself. As a kid she used to hold her breath in a hot bath; stare at a fixed spot on the floor and spin in circles until she got dizzy, falling on her back, eyes closed, making a snow angel in the carpet as Cho Halmeoni’s sewing machine whirred, Jacob at a sleepover with his friends, Cho Harabeoji drinking somewhere with his friends or passed out on the couch—her parents with their customers until they closed. She waited for company and mulled over who she’d be happier to find at the door until she remembered she was better off in her own head, at its best buzzing with light, a sense of lightness, the sound of static. Anything to prevent another collapse, folding into an inescapable ruin. Grace heard Appa talking to Umma outside, both aware they could be heard.

Why didn’t Grace care to put in more effort than they could? They knew she had her classes. Grace wanted to go out there to tell them it would be okay. But she couldn’t wade out of bed.