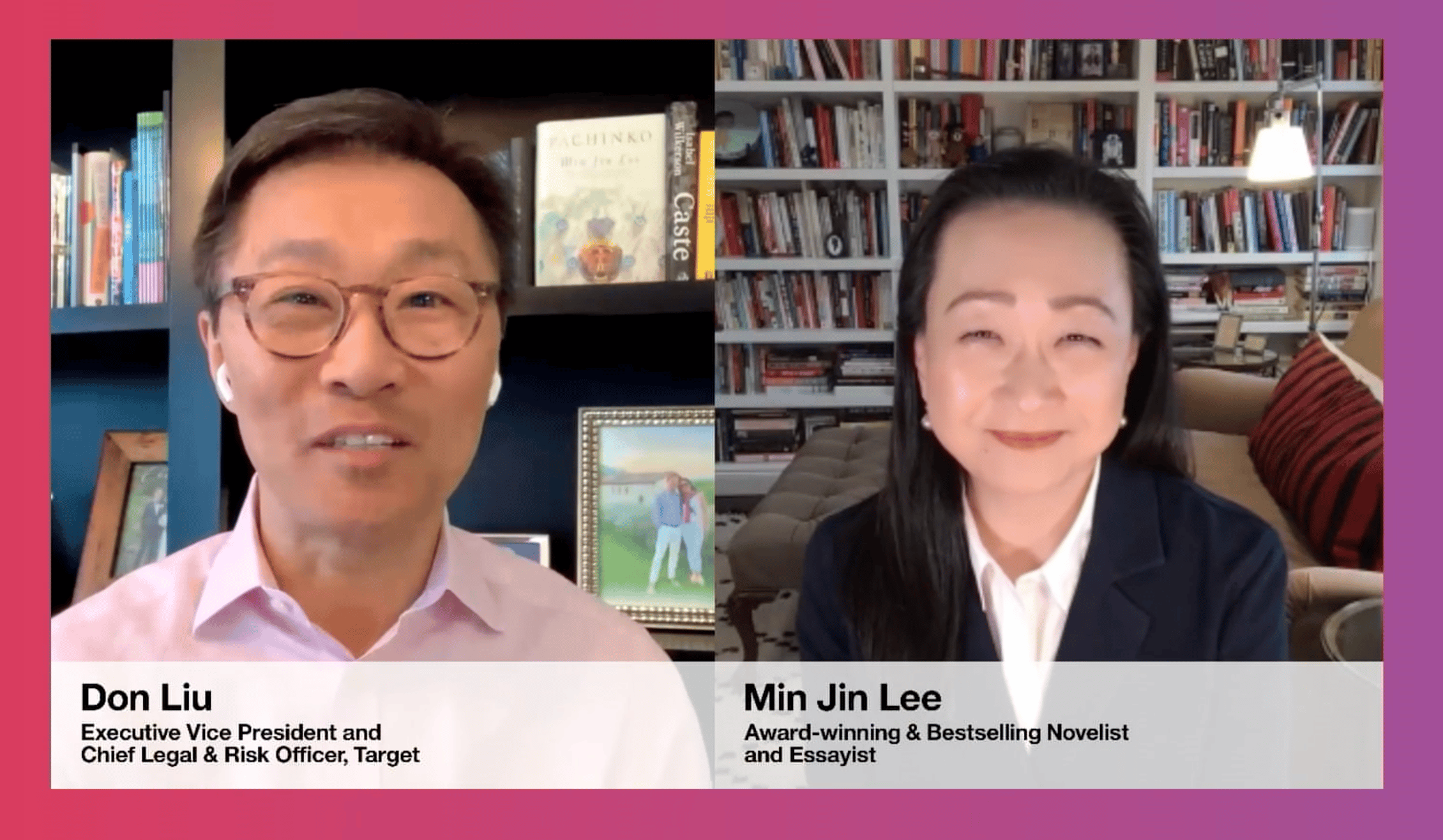

A fireside chat with Min Jin Lee, author of “Pachinko”, for the Twin Cities Asian Executive Leadership Conference.

I am so honored and delighted to have recently interviewed my friend and hero, Min Jin Lee. I first met Min Jin in May of 2017, three months after her best-selling novel “Pachinko” was published. I had read the book about a month before and was awed by this gifted Korean American writer, whom I had never heard of before “Pachinko”. After meeting her and getting to know her on a personal level, I became an even bigger fan. Don’t ask me how but she’s someone who’s both remarkably down to earth and intensely focused at the same time.

“Pachinko” went on to win numerous awards including becoming a finalist for the National Book Award and Min Jin Lee has become a bonafide literary rock star. She has also become a highly visible spokesman and leader in the Asian American community.

DL: Tell us about your childhood growing up in Queens, NY.

MJL: I came to the US in 1976 when I was 7 years old. My parents started a newspaper stand in Manhattan where I’d go on weekends with my dad. I thought it was great because I could have candy if I wanted to. After about a year of having a newspaper stand my parents became owners of a tiny wholesale jewelry store in Manhattan’s Koreatown. I worked there on the weekends and also in the summers. My parents sold costume jewelry mostly to street peddlers and shopkeepers six days a week. Growing up in Elmhurst, Queens is something that was very important and formative to me and I carry that with me always.

Such a great story because so many Asian American immigrants share a similar history. But your path from there to Yale and to law school and then to becoming a lawyer is a little less common. How much of a challenge did that present?

When you are a child of shopkeepers and all of the sudden, you become a white-collar worker in a big fancy office, it’s a different culture. It was surprising to me. Fortunately, I went to college and law school with a lot of elite people so I knew how to act the part but it wasn’t natural to me. It took me a while to figure things out. Even things like what to wear or what to say. It took me time to catch up. Thankfully most people were nice. I recall a few jerks but I suppose we all have had that.

That reminds me of my first internship after starting law school. I walked into the office of this big law firm in Philly with my best clothes on, which in my case happened to be a blue blazer and gray pants. I soon realized that I was the only male in the entire law firm, including the guy who stuffed envelopes into the mailboxes, without a full suit and tie on.

Did you go out and buy one?

I did! I called my mom and she went to Syms that very day and bought a blue suit and a gray suit. I wore those two suits every day of that summer.

How many neckties did you have?

Are you kidding? One! But we all have stories like that when you come from a family that didn’t give advice on simple things like that.

Don’t you feel grateful though? I remember when I was younger, I had one winter coat and later, when I had a couple of winter coats, I felt rich because I had more than one.

So at some point, you decided law wasn’t it and you wanted to become a writer. I’m sure your parents were worried about whether you could survive as a writer. What was the impetus behind the change and what was it like switching to a completely different profession?

I was actually a good due diligence associate so many of the law firm partners would hand me piles and piles and piles of work. I would work day in and day out and never stop because I was good at writing those due diligence memos. I was that low-level fastidious grunt you needed on your deal. One month I billed 300 hours, and I finished a big assignment and gave it to my partner, who then gave me even more work. I thought I was going to collapse.

I told my partner I couldn’t do this anymore, and I quit. I didn’t have this big plan. It was more sheer exhaustion. And perhaps a bad temper at that moment. I handed in my notice and my parents were kind of worried. But because I had a liver disease, which I had for a long time and which I don’t have anymore, I think my parents were relieved that I wasn’t going to drop dead in the office.

My husband had health insurance, and we had enough money to get by. It was doable but it was hard because I thought I could publish my book right away. It ended up taking 11 years of my life to publish one book. So I was wrong that being a writer was going to be easy.

How did you arrive at wanting to be a writer?

I’ve always written and I’m a huge reader. I thought that writing a book couldn’t be that difficult. So I thought I’ll quit being a lawyer and I’ll write an amazing novel right away and make $83,000 a year, which is what I made as a first-year associate. I was wrong. My first book manuscript was terrible.

Many people in the audience, because they saw you suddenly rise to amazing heights as the writer of “Pachinko”, think that you somehow cranked out this novel and became an overnight sensation. I know that’s not the case. Tell us about the long process that it took to arrive at your success.

Thank you for acknowledging that. Can you write a note to my publisher as to why my third book is so late because I’m sure they’d believe you?

I got the idea for “Pachinko” when I was 19, and I published it when I was 48. “Pachinko” was the first novel that I worked on but the first version was terrible so I couldn’t publish it. There was another novel called the “Revival of the Senses” which will never see the light of day because again, it was deplorable. “Free Food for Millionaires” was the third novel that I finished but it was the first that I published. And then after I moved to Japan in 2007, I started to rewrite “Pachinko” all over again. It used to be called “Motherland,” and it took me from 2007 until 2017. So I’m pathetic. It took a long time.

You’re so unusual in that you are willing to use the platform you have as an incredibly successful writer for the benefit of the larger community, particularly the Asian American community. Tell us why you do it. I’m sure it’s a risk. I’m sure your publishers get nervous when you speak up on things that are fairly controversial.

Thank you for acknowledging that. I know that you speak up also as a leader. When you’re an artist, people think that you work for yourself but when you write something you need to have a huge distribution channel. Before my book ever ends up in a reader’s hands, it goes through editors, marketing, publicity, it goes through a publisher—a publisher who is accountable to the public. And I have to deal with booksellers on a small scale like independent booksellers as well as chains and big boxes like Target, as well as Amazon and online dealers. You have all these different companies that have a point of view about my political stance.

I believe if I have any platform at all, somehow, I have to tell the truth about what I think is important. And I am a political person. That said, I’m also an introvert and a private person. I’m happy just listening to smart and talented people and clapping. But there are things that I have to say that are important. And one of the things in the past couple of years that I’ve had to highlight are the assaults and insults and the real dangers and murders of Asians and Asian Americans in this country.

As somebody who studies history, I know that contextually speaking, the recent rise of hatred and violence is not coming from zero. It’s coming from a long history of assaults and insults toward Asians and Asian Americans. And I do know that because I’m considered a credible source in the media, it’s important for me to raise my hand and say I disagree with the way things are. There are costs, and there are people who disagree with me but I think it’s worth doing this. I don’t think I could live with myself if I didn’t speak up.

I don’t think a lot of people know how active you are on anti-Asian hate crime issues and how you have engaged some of the folks in Hollywood to not only talk about it but how to remediate it. I want to thank you for that because I do think that we need more people in leadership roles like yourself to address this issue.

Thank you so much. I don’t see myself as a leader. And if you went to high school or college with me, I wouldn’t have been the one that you bet on as the leader. That said, I do think that I am a good student of history, so I’m aware that when I do speak, I speak the truth about what’s going on, and I think that may have some value.

If I could encourage those who are watching this or reading this transcript, I would say that: If you are the kind of person who is not extroverted, who doesn’t want to speak up, who doesn’t see yourself as a leader, even you can say something when you disagree; because if I can do it, surely you can.

I’m so glad you said that for the benefit of introverts. I’m an extrovert and I sometimes don’t allow other people to get a word in. But I get that question all the time from introverts. “When I’m an introvert, how do I engage when I’m uncomfortable doing so.”

Especially if you’re an introvert and you say “I disagree”, you’re actually taken more seriously because they know how hard it was for you.

A large number of our audience are in a corporate environment and want to climb the corporate ladder. You talked a bit about the risks associated with speaking up. How do they reconcile wanting to succeed on a personal and professional level and still be able to speak up?

I think it’s important to acknowledge that there are real risks to self-expression. And I never want to discount that. And even if you are good at speaking, saying things that have value takes courage. So no matter what your personality may be, just being willing to be judged takes great courage. So I acknowledge that.

Second, I think it’s important to read the room. What’s the context? Sometimes it’s better to take things offline and try to negotiate behind the scenes. Speak up but never humiliate anyone and try to never be unkind in the way you speak up.

I also think it’s important to understand that there are allies in the room. If you are paying attention to what’s important to you and to what’s important to the larger community, there’s usually one or two people in the room who will echo what you’re going to say, so that you will have greater success in your shared outcome.

Finally, I want to say something pragmatic. If you are an ambitious person, and I’m an ambitious person, too, it’s important to recognize that if you want to have extraordinary value, you’re going to have to take risks. And the risks and the rewards are often in line. If you’re not willing to take some risk for what you believe, don’t be surprised that you don’t get the rewards that follow those risks. The rewards that come are actually part of the calculus.

So obviously only talk about the things that are truly important and have value, not just to hear the sound of your own voice. But when you do take those risks, almost at a danger to yourself, know that you are fighting for something that is valuable. And possibly you, as somebody who says those things, can be somebody who is valuable.

Risk assumption is so important and yet it’s often not part of our culture. For many of us East Asians, we grew up hearing our parents tell us: don’t rock the boat, just keep your head down, do the work, and don’t offend anybody. And yet risk assumption requires some things that are contrary to what we were taught by our parents. It doesn’t come easy for Asian Americans in the corporate world to take the risks that are necessary to succeed.

Very often some people think that just talking is helpful but in that sense, I agree with the East Asians who look down at talkers. If you just talk all the time and don’t do anything, it becomes empty. That said, If you can follow up your statements with true actions and credibly live your life every day, then you become that leader.

I think a leader has to have a heart of service. And sometimes being willing to be judged for a higher truth is a form of service, especially on behalf of those who don’t have the ability to be in that room, to have that chair, to have that income or professional stability. If we can use our talents for a higher purpose then we deserve that leadership position, especially if we have that heart of service.

For those who are in the audience, many of whom are young professionals who feel they are stereotyped as model minorities or perpetual foreigners, do you have any advice on strategy to navigate their careers without being boxed in as Asians?

I think I have three ideas that are worth encouraging. Visibility. Be visible even when it’s uncomfortable for you. Be willing to be visible to other people.

The second is expression. Be willing to express yourself in writing and in speech even when you’re uncomfortable. And the more you practice, that muscle will become stronger.

The final piece is to fight tokenism. Very often you find that only one minority is accepted by the majority culture, and I want to tell you that that way of thinking will always leave us in middle management. I want to encourage you to build alliances with other communities of color and within your own community and that way you become a truly powerful community. You may have a competitive spirit but if you’re really competitive, think about how much more power you will have if you have a bigger army.

Totally true. I can’t tell you how often I am supported and empowered by those people who are allies of mine. I’m gonna wrap it up here. Thank you for being who you are. Thank you for your visibility and your outspokenness. And thank you for being an inspiration to us all.

About Min Jin Lee

Min Jin Lee was born in Seoul, South Korea and immigrated to Queens, New York with her family when she was seven years old. She studied history at Yale College and law at Georgetown University. Lee practiced law for two years before turning to writing. She teaches fiction and essay writing at Amherst College and lives in New York City.

Lee is a writer whose award-winning fiction explores the intersection of race, ethnicity, immigration, class, religion, gender and the identity of a diasporic people. Pachinko, her second published novel, is an epic story that follows a Korean family who migrates to Japan; it is the first novel written for an adult, English-speaking audience about the Korean-Japanese people. Pachinko was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction, runner-up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, winner of the Medici Book Club Prize and a New York Times 10 Best Books of 2017. A New York Times Bestseller, Pachinko was also a Top 10 Books of the Year for BBC, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and the New York Public Library. Pachinko has been translated into over 35 languages and is an international bestseller. President Barack Obama selected Pachinko for his recommended reading list, calling it, “a powerful story about resilience and compassion.”