On a cold January morning in 1890, twenty‑five‑year‑old Seo Jae‑pil stood in a Washington, D.C., courtroom and took the oath that made him the first Korean to become a citizen of the United States. In exile from his homeland, where the government had killed most of his family members, the young man had already lived through more turmoil and tragedy than most old men. That day, Seo officially adopted a new name, Philip Jaisohn, and began life as the first Korean American. There was no ceremony, no audience, and no announcement on that January day, and the significance of the occasion would only become clear decades later as Korean Americans began to build thriving communities and claim their place in the United States.

Philip Jaisohn, the first Korean American and the first Korean to become a medical doctor in the US.

A Young Reformer in a Hermit Kingdom

Seo Jae-pil was born on January 7, 1864, in Boseong, a coastal county in southern Korea. His family belonged to the Yangban class, the traditional scholarly elite, and he grew up studying Confucian texts and preparing for civil service examinations. At the age of 18, he became renowned as one of the youngest ever to pass the rigorous exams and was appointed a junior officer in the government. However, this prestige would do nothing to shield his family from the consequences of his later efforts at political reform.

Sent to Tokyo to further his education, Seo returned to his homeland convinced that his beloved but feeble country needed to modernize and reform or risk being taken over by much stronger foreign forces.

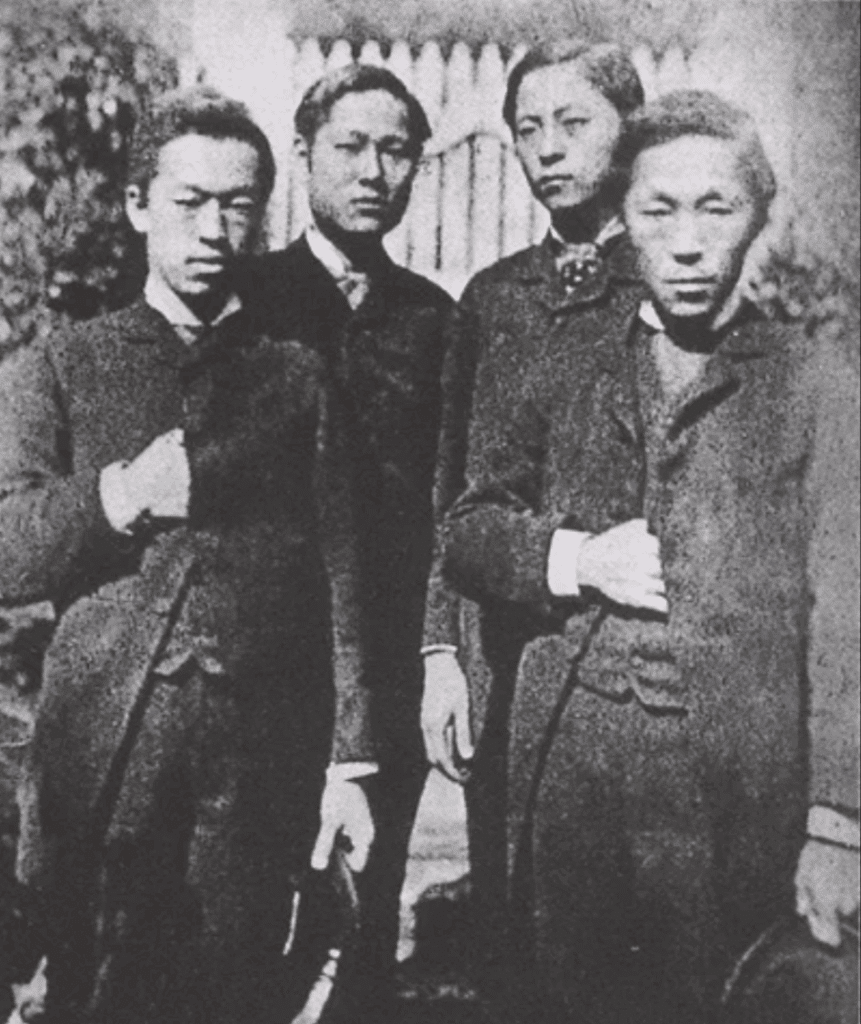

The four major players in the Kapsin Coup of December 1884. They are, from left, Park Yeong-hyo, Seo Gwang-beom, Seo Jae-pil (Philip Jaisohn), and Kim Ok-gyun.

In the late nineteenth century, Korea was very much a Hermit Kingdom with little interaction with the outside world. Resistant to modernization and vulnerable to invaders, Korea was a nation stuck in the past, where aristocrats ruled society and the oppressed commoners had almost no chance to move up the social ladder. Seo Jae-pil strongly believed in strengthening the country with democratic ideas and foreign trade and helped lead a bloody rebellion called the Kapsin Coup in 1884. After three days of fighting, the rebellion was defeated, and Seo was forced to flee the country. As retribution for the coup, many members of Seo’s family were brutally killed or sold into slavery.

Exile, Reinvention, and a New Name

After fleeing Korea, Jaisohn arrived in San Francisco with no community and no means to support himself. He was working odd jobs to survive when a reporter heard about the young Korean aristocrat working as a laborer on the docks. The reporter wrote a short article about the curious Korean refugee whose endeavors to democratize his homeland led to his exile. A wealthy industrialist named John W. Hollenbeck read the article while visiting San Francisco on business and asked to meet with Seo. Impressed by the young man’s intelligence and diligence, Hollenbeck became Seo’s benefactor, paying for Seo to move to Pennsylvania and supporting Seo’s education at the Harry Hillman Academy in Wilkes-Barre, PA.

During this time, Seo Jae-pil reversed the order of his name and adopted the Anglicized ‘Philip Jaisohn,’ which is the name he used in America from that point forward. Jaisohn moved to Washington, D.C. in 1889 and earned his medical degree in 1892 from what is now George Washington University, becoming the first Korean in the United States to become a physician. In 1894, he married Muriel Armstrong, the daughter of a U.S. Postmaster General. This was the first recorded interracial marriage between a Korean and a white American in the US.

Philip Jaisohn and Muriel Armstrong

Returning Home to Build a Modern Korea

When political conditions in Korea shifted in 1895, Jaisohn was allowed to return to his homeland. In 1896, he founded The Independent (독립신문), the first Korean newspaper printed entirely in Hangeul, to make civic knowledge accessible to ordinary people. He and his colleagues helped standardize Hangeul usage, including the introduction of modern Western-style punctuation and word spacing, which remain in use to this day.

Around the same time, he wrote to the Presbyterian Mission in Seoul offering material support for education. In one of his letters, he wrote:

“In the centre of the city of Seoul, where it is thickly settled and where as yet no mission work has been done, I own a high and desirable site containing several acres.… I will lease this to the Mission for twenty‑five years rent free or for legal purposes say a nominal rental of one dollar silver per year.… It is my desire that the school shall be an institution where manual labor is taught and where the main work shall be in the vernacular.”

This act illustrates Jaisohn’s approach to reform. He believed that lasting change required practical support, opportunities for learning, and access in a language people actually used. Education alone was not enough. It needed to be grounded in daily life and paired with material assistance. Jaisohn’s vision combined ideals with tangible action, showing that institutions could empower people as effectively as words.

A Philadelphia Home for Korean Exiles

Back in Philadelphia, he continued his work as a physician while becoming a central figure in the Korean community. Many Koreans arrived in the city as students, political exiles, or laborers connected to missionary and diplomatic networks. Jaisohn’s home and office became a place to find help with language, healthcare, and navigating life in a new country. He also engaged in the printing business, which allowed him to spread his ideas for the democratization of Korea.

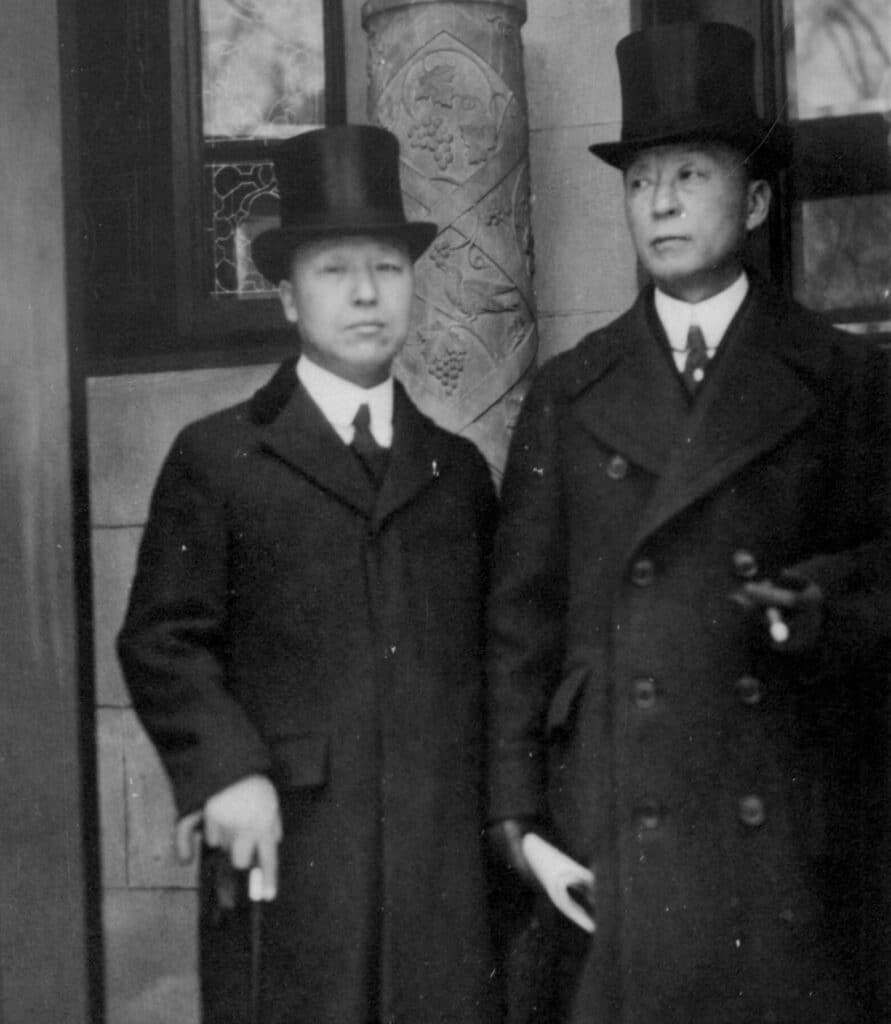

After the “March 1st Movement” in Korea in 1919, Jaisohn helped organize the First Korean Congress in Philadelphia to protest the Japanese colonization of Korea. Delegates, including Syngman Rhee, came from across the country to discuss Korea’s fight for independence. Jaisohn led many public gatherings in which he carried both American and Korean flags, demonstrating that allegiance to his adopted country could coexist with advocacy for his homeland. He also founded the Korea Review, an English-language journal designed to explain Korea’s independence movement to Americans and build broader support.

Syngman Rhee (left) and Philip Jaisohn (right) at the Korean in Washington, D.C, 1921

After World War II, Jaisohn returned to a newly independent Korea to serve as chief advisor to the U.S. military government. Political divisions and frustration eventually brought him back to Pennsylvania, where he continued to practice medicine until his death in 1951. He was posthumously honored with the National Foundation Medal by the Korean government in 1977, and his ashes were interred in Seoul’s National Cemetery in 1994.

Carrying On Jaisohn’s Legacy

Founded in 1975, the Philip Jaisohn Memorial Foundation carries on his life’s work. I was honored to serve as the seventh president of the Foundation from 2003 to 2006 and to contribute, in a small way, to preserving Dr. Jaisohn’s enduring legacy. The foundation began as a small medical clinic for Korean immigrants and has grown into an organization providing medical care, social services, leadership programs, and cultural education. The Jaisohn home in Media, PA, is now a museum where people can view many artifacts from his life and times. It remains a living record of the earliest Korean American community in Philadelphia and the life of the man who helped create it.

Philip Jaison and his wife at his home in Media, PA.

On May 21, 1994, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and the Philip Jaisohn Memorial Foundation dedicated a historical marker for Jaisohn, stating:

Philip Jaisohn, American-educated medical doctor who sowed seeds of democracy in Korea, published its first modern newspaper (1896-98), and popularized its written language. The first Korean to earn a Western medical degree and become a U.S. citizen. He worked for Korean independence during the Japanese occupation, 1910-45. Chief Advisor to the U.S. Military Government in Korea, 1947-1948. This was his home for 25 years.

Philip Jaisohn House Museum, Media, PA

Philip Jaisohn’s life shows the ways one person can connect two countries through education, service, and community. He claimed citizenship, pursued knowledge, and built institutions that served others. He created spaces where ordinary people could learn, speak, and act according to their beliefs. On Korean American Day, the story of Philip Jaisohn, the first Korean American, reminds us of the power of one man’s fortitude, persistence, and relentless service.